The General Assembly of the Istanbul Arbitration Centre (“ISTAC”) unanimously approved the ISTAC Arbitration Rules (“Rules”) on 26 October 2015. In this guide, we review the ISTAC’s Rules, its fast track arbitration mechanism, Emergency Arbitrator system, fee structure, compare the Rules with several established arbitral institutions, as well as discuss areas where the Rules may develop in future.

The ISTAC’s Rules are available on the ISTAC’s official website.

Istac’s Influences And Similarities With Other Arbitral Rules

The Rules are generally compliant and sit well alongside those issued by high profile arbitration centers around the world. The ISTAC appears to be heavily influenced by the ICC Arbitration Rules, along with lessons learnt by other international arbitration bodies. The Rules are notably similar to the ICC Rules of Arbitration, except for provisions regarding fast track arbitration.

The ICC has a long history in Turkey, so local parties and practitioners are already familiar with the ICC Rules. Statistically, Turkish parties have usually opted for ICC arbitration and disputes involving Turkish parties are usually taken to the ICC. Therefore, it is understandable why the ISTAC has introduced arbitration rules which are substantively similar to the ICC’s rules.

During drafting, the ISTAC appears to have taken into account revisions which other arbitral bodies made to their respective rules over time. Accordingly, the Rules benefit from the results of many discussions and experience-based amendments which have occurred in wider international commercial arbitration.

Istac’s Points Of Difference

Institutional arbitration has been widely criticized in terms of its effectiveness, pace, fees, and flexibility. Similarly, arbitration has globally faced serious questions about the impartiality, availability and expertise of arbitrators. These factors have damaged arbitration’s overall attractiveness as a dispute resolution mechanism.

Against this background, the ISTAC offers:

- A similar (but less bureaucratic) institutional supervision system for arbitrations.

- An effective Secretariat.

- Fast track arbitration procedures.

- Appointment of emergency arbitrators.

- Flexible and relatively low fee structure, compared to regional and international bodies.

The ISTAC’s fee levels and structure have already received positive feedback. Application fees are calculated on a pro-rata basis, relative to a case’s quantum (discussed in detail below). The ISTAC’s fees are low compared to regional and international arbitration bodies. The ISTAC aims to provide high-quality dispute resolution services faster and cheaper than Turkish commercial courts.

The competitive fee structure is potentially ISTAC‘s biggest marketing strength. However, when parties test an arbitration institution over time, it is service quality, impartiality and continuity which become more important factors than fees alone.

Overview Of Istac’s Rules

The ISTAC’s Rules will apply if the parties explicitly decide their dispute will be resolved in accordance with these rules [Article 2/1, Rules]. The Rules will apply even if the parties use different expressions in referring to the ISTAC, provided it is understood that the parties decided to take their disputes to the ISTAC [Article 2/2, Rules].

According to the Rules, arbitration begins when the initiating party files its formal Request for Arbitration to the ISTAC Secretariat, in the required number of copies, as well as deposits the application fee [Article 7, Rules].

The initiating party can also directly lodge its Statement of Claim with the ISTAC Secretariat, rather than first requesting an arbitration [Article 7/7, Rules]. In such a case, the respondent can either:

- Submit its Statement of Defence within 30 days; or

- Submit an Answer to Request for Arbitration.

The arbitration will continue in accordance with the Rules even if the respondent does not participate, appeals the decision to arbitrate, or does not answer the Arbitration Request [Article 8/5, Rules].

The respondent can file counterclaims in its Answer to Arbitration Request, provided it deposits an application fee, as set out in Annex 3 to the Rules [Article 8/7, Rules]. In this case, the claimant may further submit its responses to the respondent’s counterclaims within 30 days of its notification of the Answer to Request for Arbitration.

The respondent must submit any appeal about the existence, validity, content, scope or implementation of the Arbitration Agreement within its Answer to Arbitration Request, or else the jurisdiction appeal will not be considered [Article 9, Rules].

Parties have discretion to determine the number of arbitrators [Article 13/1, Rules]. If the parties wish to appoint more than one arbitrator, an uneven number of arbitrators must be selected. If the parties have not agreed on the number of arbitrators, then the ISTAC’s Board of Arbitration (the “Board”), taking into account all the relevant circumstances, will decide that the dispute will either be resolved by a Sole Arbitrator or by an Arbitral Tribunal consisting of three arbitrators [Article 13/2, Rules].

The Board is an independent body of the ISTAC, consisting of Istanbul Arbitration Centre National Board of Arbitration and the International Board of Arbitration. The Board is responsible for administering the application the ISTAC’s Rules of Arbitration, and resolution of disputes in accordance with the Rules.

Where the dispute is to be resolved by a Sole Arbitrator, the parties must agree on the specific arbitrator together. If the Parties are unable to agree within 30 days of the Claimant’s Request for Arbitration being notified to the opposing party (or within any extension granted by the Secretariat), the Board will appoint the arbitrator [Article 14/1, Rules].

If a dispute is to be resolved by Arbitral Tribunal, each of the parties must select an arbitrator in their respective Request for Arbitration and Answer to Request for Arbitration. If a party does not select an arbitrator, the Board will appoint the arbitrator [Article 14/2, Rules].

Unless the parties agree otherwise, the two selected (or appointed) arbitrators will jointly determine the third arbitrator. If the two arbitrators do not determine the third arbitrator within 15 days of the date the Secretariat notifies them of their selection or appointment, the Board will appoint the third arbitrator [Article 14/3, Rules].

Parties can challenge an arbitrator’s selection if [Article 12, Rules]:

- The arbitrator does not have the qualifications agreed upon by the parties.

- Any circumstances and conditions justify doubts about the arbitrator’s impartiality and independence.

- Some other reason prevents the arbitrator from fulfilling his/her duty.

The Sole Arbitrator or the Arbitral Tribunal must conduct the arbitration in accordance with the Rules. Any rules agreed by the parties will apply to situations where the Rules are silent. In the absence of an agreement between the parties, rules determined by the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal will apply [Article 22, Rules].

Arbitrations will occur in Istanbul unless the parties agree otherwise. However, unless the parties agree otherwise, the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal can, upon consultation with the parties, conduct hearings and meetings at any location which they consider appropriate [Article 23, Rules].

The parties have discretion to determine the arbitration language. In the absence of agreement between the parties, the Sole Arbitrator or the Arbitral Tribunal will determine the arbitration’s language, taking all the relevant circumstances and conditions into account. Arbitrations can be conducted in more than one language [Article 24, Rules].

The Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal must apply the selected rules of law to the merits of the dispute. In the absence of agreement between the parties about which rules of law should apply, the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal will apply the rules of law which it determines to be appropriate. The Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal will assume the powers of an amiable compositeur or decide ex aequo et bono only if the parties have agreed to give the arbitrators such powers [Article 25, Rules].

After consulting with the parties, the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal can appoint one or more experts, define their terms of reference and receive their reports. The arbitrators and the parties can question the expert at a hearing [Article 29, Rules].

In principle, the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal can hold hearings either at the parties’ request, or of its own motion. However, after consulting the parties, the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal can also render a decision based on documentary evidence alone, without holding a hearing [Article 30, Rules].

Unless the parties agree otherwise, if a party requests an urgent measure, the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal can order any interim measure which it deems appropriate [Article 31/2, Rules].

Before sending the file to the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal (and in appropriate circumstances after sending the file), the parties can apply to any competent court for interim measures. A party’s application to court for such measures will not be deemed to be an infringement or a waiver of the Arbitration Agreement and will not affect the powers reserved to the Sole Arbitrator or the Arbitral Tribunal [Article 31/4, Rules].

As soon as possible after the last hearing concerning the matters to be decided in an award, or after filing the last authorized submissions (whichever is later), the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal must:

- Declare the proceedings closed with respect to the matters to be decided in the award; and

- Inform the Secretariat and the parties of the date by which it expects to submit the draft award.

After proceedings are closed, no further submission or argument can be made, nor evidence produced, with respect to the matters to be decided in the award, unless requested or authorized by the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal [Article 32 of the Rules].

The Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal must render its final award within six months. The period begins on the date of the last signature by the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal, or by the parties, on the Terms of Reference. Alternatively, if Article 26/4 applies, the period begins on the date the Secretariat notifies the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal that the Board has approved the Terms of Reference [Article 33/1, Rules].

Where the parties agree not to draw up the Terms of Reference, the period begins on date the procedural time table is delivered to the Secretariat [Article 33/1, Rules]. The Board can extend the period pursuant to a reasoned request from the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal, or at the Board’s own initiative if it determines an extension is necessary [Article 33/2, Rules].

If the arbitral tribunal includes more than one arbitrator, an award is made by a majority decision. If no majority is established, the award will be made by the president of the arbitral tribunal alone [Article 34, Rules].

The Secretariat will notify to the parties once the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal has made a signed award, provided the arbitration costs have been fully paid [Article 36, Rules]. All awards are binding on the parties.

Where the parties reach a settlement after the file has been sent to the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal, the settlement can be recorded in the form of an award, made by consent of the parties, if the parties request this and the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal agrees [Article 38, Rules].

Arbitrations will be terminated if [Article 39, Rules]:

- The claimant withdraws its case, except where the tribunal accepts a claim by the respondent that legitimate interest exists in obtaining a final decision from the tribunal about the dispute.

- The parties agree on termination.

- The Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal decides that proceeding with the arbitration is unnecessary or impossible.

- Advance payments are not deposited with the Secretariat.

The Board and its members, the Secretariat and its members, ISTAC employees, arbitrators and other persons who are appointed by the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal, will not be liable to any person for any act or omission in connection with the arbitration, except to the extent such limitation of liability is prohibited by law [Article 44, Rules].

Fast Track Arbitration Under Istac

Unlike a majority of international arbitral institutions, the ISTAC has introduced a separate fast track system, in addition to its normal Rules. The move is encouraging and sufficiently self-explanatory for Turkish users, who are traditionally sceptical towards arbitration. Since Turkish commercial courts are notorious for their slow pace and inefficiency, the expedited process might be the factor which sways parties towards the ISTAC.

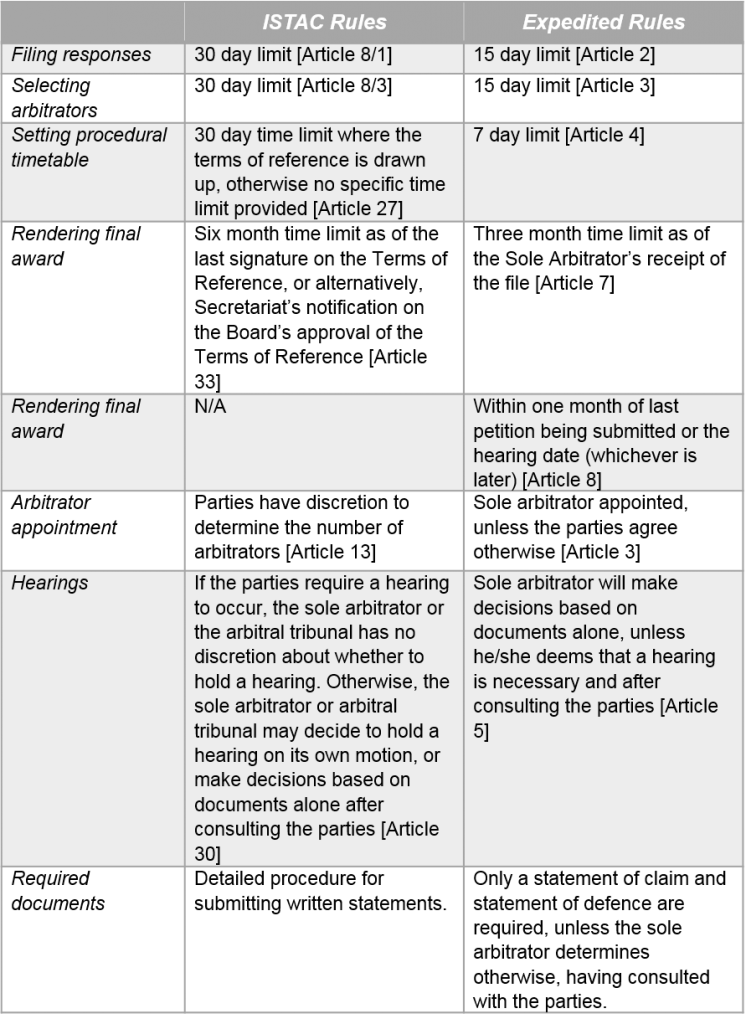

Unless parties agree otherwise, the ISTAC’s Fast Track Arbitration Rules (“Fast Track Rules”) will automatically apply to disputes where the total claim amount and claims within the counterclaim (if any) are less than TRY 300,000 (on the date the arbitration commences). However, parties can agree to apply the Fast Track Rules for disputes exceeding this amount [Article 1, Fast Track Rules].

Other arbitral institutions (for example, SIAC) still regard expedited rules as an exception, which the parties must request in order to be applied.

The Fast Track Rules substantially shorten and simplify the normal procedure set out in the ISTAC’s normal Rules. Key points of difference are noted in the table below:

Emergency Arbitrator Mechanism Under Istac

The ISTAC has followed recent international trends and introduced Rules for Emergency Arbitrators (“Emergency Rules”). The Emergency Rules represent another effort by the ISTAC to be the most modern arbitral institution in the region, capable of addressing urgent matters. The Emergency Rules are attached to the Rules as Annex 1.

The Emergency Rules will apply if a party applies to the Secretariat to appoint an Emergency Arbitrator before the file has been sent to a Sole Arbitrator or the Arbitral Tribunal. Parties can agree in advance that the Emergency Rules will not apply.

The Emergency Rules do not prevent any party from seeking interim conservatory measure from the courts, either before or after applying for an Emergency Arbitrator. Court application for such a measure should not be deemed to be an infringement or waiver of the Arbitration Agreement, or a waiver of the right to apply for an Emergency Arbitrator [Article 1/3, Emergency Rules].

The party applying to appoint an Emergency Arbitrator will not be required to submit a Request for Arbitration, Statement of Claim, Answer to the Request for Arbitration, or Statement of Defence [Article 2/1, Emergency Rules]. However, if the party requesting the Emergency Arbitrator does not submit a Request for Arbitration or Statement of Claim within 15 days of the Secretariat receiving the request, the Board’s President will terminate the emergency arbitrator proceedings [Article 2/5, Emergency Rules].

The President of the Board will appoint an Emergency Arbitrator within two days of the Secretariat receiving an application. No Emergency Arbitrator will be appointed after the file has been sent to the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal, pursuant to Article 18 of the Rules.

An Emergency Arbitrator will not act as an arbitrator in any arbitration relating to the dispute which gave rise to the application made for the Emergency Arbitrator unless the parties agree otherwise. [Article 3/5, Emergency Rules].

After the file has been sent to the Emergency Arbitrator, all written communications between the parties must be submitted directly to the Emergency Arbitrator, with copies sent to the other party and the Secretariat [Article 3/7, Emergency Rules].

The Emergency Arbitrator will establish a procedural timetable for the emergency proceedings within two days of being sent the file. The Emergency Arbitrator makes a decision based on documentary evidence alone, without holding a hearing [Article 6, Emergency Rules].

The Emergency Arbitrator determines whether an emergency arbitration application is admissible and whether he or she has jurisdiction to order emergency measures [Article 6/2, Emergency Rules].

The Emergency Arbitrator must issue his or her decision within seven days of being sent the file. The President of the Board can extend the time, on receipt of a reasoned request from the Emergency Arbitrator, or at his or her own initiative [Article 7/1, Emergency Rules].

The Emergency Arbitrator’s decision is binding on the parties and applies with immediate effect [Article 7/4, Emergency Rules].

The Emergency Arbitrator’s decision will cease to be binding on the parties if:

- The President terminates the emergency arbitrator proceedings.

- The Board accepts a challenge against the Emergency Arbitrator.

- The Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal makes a final award unless the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal expressly decides otherwise.

- The arbitration is terminated before a final award is given.

The Emergency Arbitrator can make a decision subject to whatever conditions he or she sees fit, including requiring parties to provide financial securities [Article 7/2, Emergency Rules]. The Secretariat will not process an application without receiving proof of paying these expenses [Article 8/2, Emergency Rules].

Applicants seeking an Emergency Arbitrator must pay TRY 40,000, consisting of TRY 10,000 for the ISTAC’s administrative expenses and TRY 30,000 for the Emergency Arbitrator’s fees and expenses. The Secretariat will not send an application to an Emergency Arbitrator until it receives the TRY 40,000.

An Emergency Arbitrator’s decision will state the costs of the emergency proceedings and a decision on how these costs should be apportioned between the parties. If a party requests, the Sole Arbitrator or Arbitral Tribunal can later amend the Emergency Arbitrator’s decision about costs.

Istac’s Costs And Fees

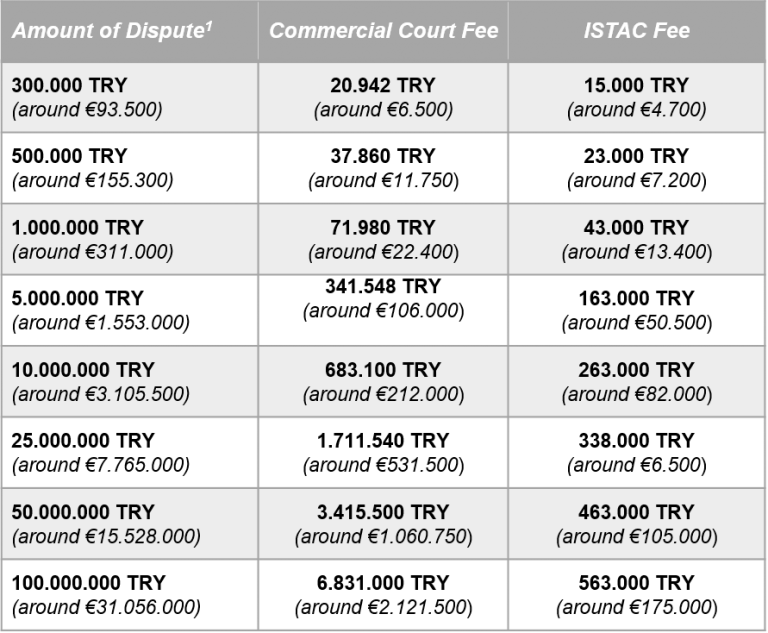

The ISTAC’s competitive fee structure could potentially attract many market players, seeking to avoid high official costs associated with other dispute resolution forums such as commercial courts and other arbitration institutions.

The ISTAC generally follows the fee structure established by the ICC, although the ISTAC’s tariff appears to be more cost efficient for lower-value disputes. However, the ISTAC’s Tariff is occasionally slightly higher than the ICC’s, due to each structure using different dispute limits.

The ISTAC’s fees by comparison to Turkish Commercial Courts can be seen in the table below.

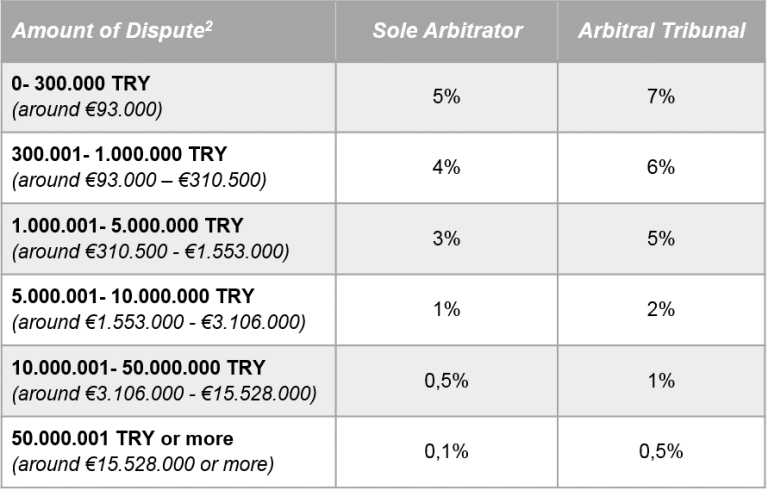

The ISTAC’s tariff for arbitrators is also reasonable compared to other institutions. Arbitrator fees are determined pro-rata to the amount of the dispute, with a minimum arbitrator fee of 2.000 TRY (Annex 3 of the Rules).

Parties should bear in mind that those fees exclude any tax liability which arbitrators face. Therefore, in practice, an additional 18% to 22% will be added to an arbitrator’s fee, depending on VAT and stoppage requirements.

The stakes are generally high in issues which are taken to arbitration. Therefore, despite attractive fees, service quality remains the primary factor for parties when considering whether to use the ISTAC. The ISTAC’s lure of lower fees will become ineffective if the service proves to be low quality.

Service quality has several dimensions for arbitration institutions. The ISTAC has taken a considerable step towards ensuring quality by establishing a list of well-known, experienced and respected arbitrators for international and local disputes. For now, Prof. Dr. Ziya Akıncı is named as the President of the centre. Prof. Dr. Bernard Hanotiau, Jan Paulsson, Dr. Hamid Gharavi and Asst. Prof. Dr. Candan Yasan have been announced as being amongst the ISTAC’s International Board. Prof. Dr. Sabih Arkan, Dr. Cemile Demir Gökyayla, Atilla Altop and Dr. Candan Yasan will act as the National Board.

The prestige, experience and neutrality of these names is indisputable. These individuals will help develop a culture of arbitration in Turkey through the respect they hold internationally, ultimately benefitting the ISTAC.

Commentary

The short time limit imposed for granting an arbitral award is one of the ISTAC’s key advantages for users. Concerns about timelines are understandable in a jurisdiction where commercial cases before courts might take anywhere between two and ten years to finalize.

The pace and inefficiency of arbitral institutions have been widely discussed. Introducing expedited arbitrations is a promising feature for the ISTAC and seems to reflect its intention to establish an efficient system, delivering relatively faster awards. It also indicates the ISTAC’s mindset about how it wants to position and differentiate itself in the region, amongst other arbitral institutions and the Turkish courts.

The ISTAC’s approach to the expedited procedure is also encouraging. For disputes below a certain amount, the ISTAC does not wait for the parties to request an expedited process. Instead, the ISTAC begins trying those lower-value cases according to expedited rules automatically. Expedited rules are still exceptions for many arbitral institutions, requiring party initiation. Therefore, the ISTAC’s practical approach in this respect deserves recognition.

Parties can request appointment of an Emergency Arbitrator and detailed procedures are established for emergency arbitrators. These factors again illustrate the ISTAC’s intention to pragmatically address urgent issues in an efficient manner, without forcing parties to seek interim decisions before the courts.

The ISTAC’s rules require the arbitral tribunal to prepare a procedural timetable, including aspects such as dates for hearings, submissions and other procedural events. The timetable is prepared on consultation with the parties. The approach seems to have been improvised from the ICC’s rules. However, the ISTAC’s lack of a “Case Management Conference” for parties to share their opinions on the arbitration proceeding and to agree upon procedural matters, should be seen as point for future development.

The ISTAC’s Rules allows new claims to be introduced, even after the terms of reference are signed or approved by the Board. However, amendments to claims and defenses are not regulated under the Rules. Few arbitral institutions offer these elements. Arguably, such flexibilities could prolong proceedings due to parties abusing the process. However, the six-month time limit applied for the tribunal to render the arbitral award following the Secretariat notifying the terms of reference to the arbitral tribunal could address any concerns in that respect.

On the other hand, disputes with international elements may require immediate communication by distant parties and persons, offering such methods to users will be an advantage in that it prevents loss of time due to communication methods and travel. However, the Rules do not include any provision related to these methods. The ISTAC’s Rules seem to improve adopting relevant rules of ICC in this respect. The provisions in Appendix IV of the ICC Arbitration Rules (titled “Case Management Techniques”) allow meeting or hearing to be held via media, such as teleconference or video conference. While hardly any international arbitration centres offer these options to the users, we believe the ISTAC will find this element to be a necessity.

From an institutional point of view, the fact that ISTAC has two Boards, National Arbitration Board and International Arbitration Board, may not be a mainstream method. However, it indicates two issues that the ISTAC wishes to address. The first point is that the ISTAC principally would like to attract local users and disputes. Turkish parties are frustrated by the ineffective court system. A good reliable alternative could be their first choice in case of disputes. The second point is that local disputes could be different in nature compared to international ones. Also, the dynamics and culture of local disputes are different in nature. Therefore, the National Arbitration Board of the ISTAC could be better positioned to address local issue that might arise and respond to the needs of Turkish parties. Such an approach will ultimately help improve the reliability and trustworthiness of the ISTAC, sooner rather than later.

Unlike major arbitral institutions, the ISTAC hesitates to claim a confident exclusivity in the appointment of arbitrators to the extent possible. In fact, the authority of arbitration institutions over the selection of arbitrators is undeniably significant in that the quality of arbitrators appointed for the cases determines the success of institution too. For this reason, prestigious arbitration institutions such as ICC or LCIA claim strict exclusivity and have the final word in the appointment of arbitrators. ISTAC may have wanted to give as much freedom as possible to the parties for the appointment arbitrators to eliminate concerns about ambiguity over the arbitrators who will try their cases. Such flexibility may perhaps be at the expense of its institutionalism, efficiency and reputation, particularly in the long run.

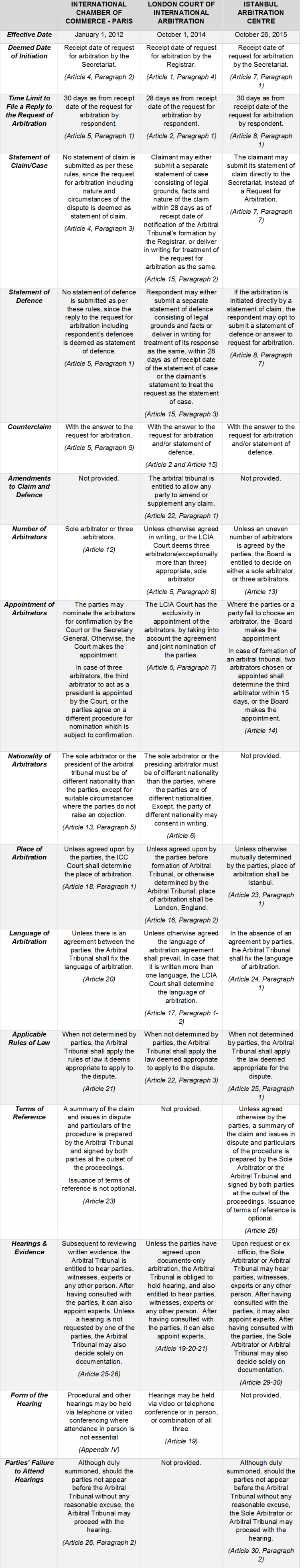

Comparison Table: Icc, Lcia, Istac

The table below compares the arbitration rules from:

- International Chamber of Commerce – Paris

- London Court on International Arbitration

- Istanbul Arbitration Centre

1. As of 2 February 2015, 1 Euro equals to 3,22 Turkish Liras.

2. As of 2 February 2015, 1 Euro equals to 3,22 Turkish Liras.