The Use of Paperless Trade and Electronic Signatures

Following the Covid-19 pandemic, a concept referred to as the “new normal” lifestyle has emerged as a widely used term to describe the global changes that have taken place. This new normal has fundamentally altered our daily lives on both social and personal levels, leading to the abandonment of traditional methods. The changes brought about by Covid-19 have shaped this new normal and directed businesses towards a more innovative, digitally-focused, and flexible structure. Particularly, the impact of the new normal on paper-based business models has become evident as businesses have shed their old habits. Paperless trade can be defined as the digitalization of information flow processes and the provision of commercial information and documents – required between relevant parties – in electronic format. In other words, paperless trade refers to the conduct of trade using electronic data instead of physical documents. In today’s interconnected world, paperless trade plays a significant role in reducing commercial costs and enhancing the efficiency of commercial activities.

A paper-independent trading system directly affects the swift transport and delivery of goods. It also offers advantages in terms of compliance with legal regulations for individuals and businesses. Furthermore, the use of paperless trade contributes to a more transparent and traceable economic operation for traders as well as governments and consumers. For instance, paperless trade contributes to combatting counterfeiting, illegal commercial activities, and money laundering by increasing the visibility of exported goods.[1] Another example of the effective use of paperless trade is the United States during the new normal period. For the first time, the state of New York has enacted a groundbreaking law that allows electronic signatures and electronic document approval for those preparing tax returns. This has eliminated the requirement for these documents to be physically signed by tax return preparers.

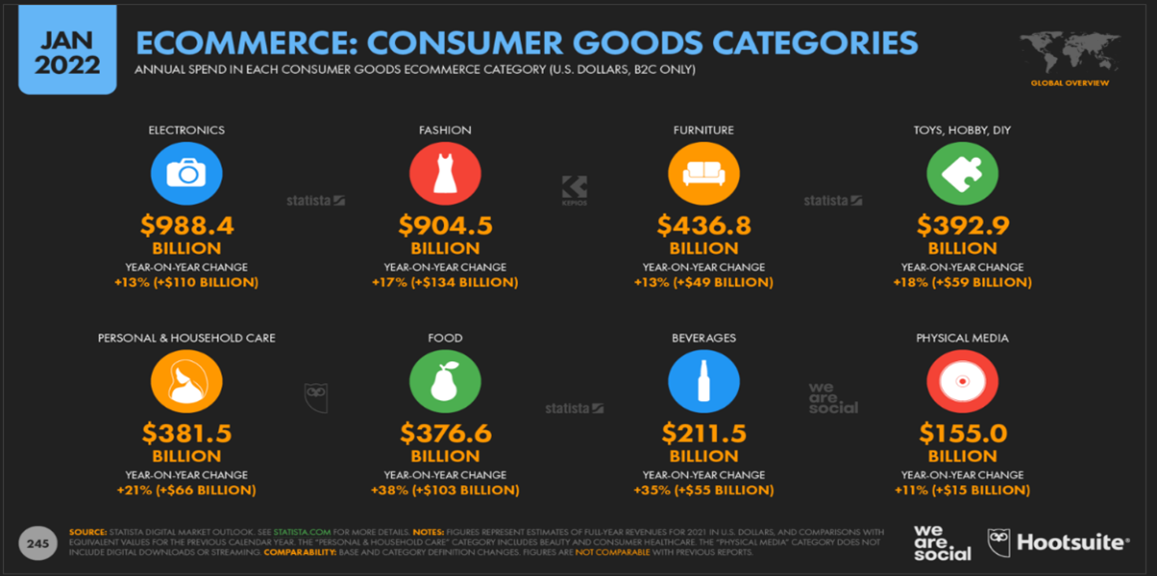

From the perspective of consumers, online transactions have become increasingly widespread due to the global pandemic, serving as an effective means of purchasing goods during quarantine and becoming an integral part of consumer behavior in the new normal.

( https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-global-overview-report )

While paperless trade offers many advantages, the biggest concern in this regard is the need for local rules and regulations to be established. The validity of electronic documents for the purpose of benefiting from paperless trade must be legally regulated. In paper-based transactions, the method used by parties to establish the validity of a contract is a handwritten signature, whereas in paperless trade, the validity of the contract depends on the validity of an electronic signature (“e-signature“).

In the context of the new normal, the global momentum gained by paperless commercial activities has made the use of electronic signatures (e-signatures) critically important. Currently, many countries, including Turkey, have regulations on e-signatures to support the development of digital commerce.

UNCITRAL Model Law on E-Signatures with E-signature Applications

E-signatures have started to replace wet signatures in many countries due to their ability to facilitate contract formation. E-signatures; however, require additional measures concerning security, identity verification, and authenticity compared to wet signatures. Some countries have implemented detailed e-signature regulations to address these concerns. To summarize the historical developments in this regard, the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (“UNCITRAL”) has prepared the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Commerce (“MLEC”) regarding electronic commerce. During the same period, the European Union (“EU”) issued Directive 99/93/EC on Electronic Signatures (“EU Directive“), providing a legal framework for e-signature use in EU member states. The EU Directive became obsolete with the publication of Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market (“eIDAS“) on 1 July 2016.

Because the EU Directive set goals for EU member states in terms of e-signature regulations, member states were required to establish national legal regulations in parallel with this directive. They also needed to define competent national authorities, inspection mechanisms, and sanction regimes accordingly. To achieve this goal, UNCITRAL prepared the Model Law on Electronic Signatures (“MLES”) in 2002.

Similar to the EU Directive, MLES also clearly distinguishes between digital and electronic signatures. While a simple e-signature is legally valid, a digital signature has the same legal effect as a wet signature. While a digital signature verifies the accuracy of an electronic document, a simple e-signature is a symbol that serves as evidence of the user’s intent to sign the electronic document. Shortly after the publication of the EU Directive and MLES, Turkey enacted Law No. 5070 on Electronic Signatures (“E-Signature Law“) on 14 October 2004, which was published in the Official Gazette numbered 253551. The E-Signature Law was prepared in accordance with the provisions of the EU Directive and MLES.

Under the E-Signature Law, a secure e-signature is defined as follows:

- It is exclusively linked to the signature holder.

- It is created using a secure electronic signature creation device that is solely under the control of the signature holder.

- It is based on a qualified electronic certificate that verifies the identity of the signature holder.

- It enables the determination of whether any subsequent changes have been made to the electronically signed data.

Additionally, an e-signature must be based on a qualified electronic certificate provided by electronic certificate service providers (“CSPs“) authorized by the Information Technologies and Communication Authority (“ICT“).

A qualified electronic certificate must contain the following information:

- Identification details of the certificate service provider and the country where it is established.

- Identifying information of the signature holder.

- The start and end dates of the certificate’s validity period.

According to Article 5 of the E-Signature Law, an electronic document containing a secure electronic signature is legally valid. The current Code of Civil Procedure also adopts a similar approach. The legal boundaries of e-signature applications are also specified in Article 5 of the E-Signature Law. According to this article, legal transactions subject to formal requirements or special ceremonies prescribed by laws and collateral agreements other than bank guarantee letters cannot be performed with a secure electronic signature.

Furthermore, on 3 February 2021, Law numbered 7263 on Technology Development Zones and Amendments to Certain Laws introduced significant changes within the framework of e-signature regulations.

As a result of the recent changes in the E-Signature Law, Certification Service Providers (CSPs) will be able to remotely and reliably verify the identity of individuals to whom they issue qualified certificates through Turkish identity cards (TC identity cards). Additionally, electronic seals have been regulated. Definitions for electronic seals and electronic seal holders have been added within the scope of these changes, clarifying the legal nature of electronic seals. With these changes, an electronic seal will be considered to have the same legal status as an official seal and any other physical seal. Unauthorized acquisition of seal creation data or seal creation tools without the consent or request of the seal holder is considered a crime. If CSPs violate their obligations regarding electronic seals, they may be subject to imprisonment ranging from one (1) to three (3) years and a judicial fine of no less than fifty (50) days.

Electronic Seal

With the aim of determining the procedures and principles for the acceptance of electronic seal certificate applications, the creation, use, cancellation, and renewal of electronic seal certificates, as well as the procedures and principles for electronic seal creation and verification, the Regulation on Procedures and Principles Regarding Electronic Seals has come into effect on 14 September 2022. Thus, the definition of an electronic seal (“E-seal“) has been established as “electronic data added to another electronic data or logically linked to electronic data and used to verify the information of the electronic seal holder.” It has been regulated that the E-seal will have the same legal status as a physical seal.

Within the E-seal, a distinction has been made between secure E-seals and advanced E-seals. The identification of the E-seal holder will be based on the official title and MERSIS number specified in official records or provided by Electronic Certificate Service Providers (“ECSH”), similar to the regulations for electronic signatures. Additional information on this topic can be found in the Moroğlu Arseven Gazette publication dated 28 October 2022.

In the EU, within the scope of eIDAS, three (3) types of signatures have been defined as follows:

- The first type is known as a simple e-signature. A simple electronic signature includes all electronic data that is either attached to or logically associated with other electronic data used by the signature holder in the signature process. For example, signing a document on a tablet computer or scanning a wet signature can be cited as an example of a simple electronic signature that is not regulated under the E-Signature Law.

- The second type, an advanced e-signature, is a type of e-signature that meets specific criteria outlined in eIDAS Article 26, providing a higher level of identity verification for the signature holder, security, and tamper-sealing. As not all privacy conditions specified by the E-Signature Law; however, may be met by advanced e-signatures, their validity can be rejected under the E-Signature Law.

- The third type of signature is a qualified e-signature. This type of signature is considered equivalent to a handwritten signature and is the only type with a special legal status in EU member states. A qualified e-signature must meet certain specific conditions and be supported by a qualified certificate. The qualified certificate must be issued by a reliable service provider (“GHS“) that has been declared in the EU Trusted List and approved by an EU member country. A qualified e-signature has the same legal effect as a wet signature under the E-Signature Law.

During the implementation of e-signatures, the accuracy of the signature is ensured by a GHS. The status of GHS is defined under eIDAS as “a natural or legal person offering one or more qualified or non-qualified trust services.” GHSs are approved by EU member countries and announced in the EU Trusted List. In the context of MLES, the digital signature provided by SHS serves the same role as GHS. Under the E-Signature Law; however, SHSs are regulated and supervised by the ICT.

The primary function of GHSs is to verify the accuracy of the digital signature and ensure the existence of the verification. These aspects are crucial for using the signature as evidence in court. During the processes of creating, validating, and safeguarding e-signatures, GHS plays a critical role. This; however, role also raises certain privacy concerns.

The participation of GHS in extensive data sets and Big Data necessitates their operation in compliance with data protection regulations.

During the process of creating an e-signature, GHS acquires valid seals at the relevant date and time. This ensures that the timing of the signature becomes conclusive when it comes to the control of the document or signature by competent authorities.[2] Furthermore, for it to be legally binding, the e-signature must also include the time stamp provided by GHS.

Differences Between Advanced and Qualified E-Signatures

The fundamental differences between advanced and qualified e-signatures can be examined across three stages: legal assurance, evidentiary strength, technical security, and cost.[3]

A qualified e-signature includes the burden of proof in its favor. In other words, unless evidence to the contrary is presented, a qualified e-signature is presumed to have been signed by the signatory. On the contrary, for simple or advanced e-signatures, the burden of proof is reversed. In a situation where the identity of the signatory is questioned, the burden of proof falls on the person claiming that the signature is genuine. Therefore, for documents and contracts that may involve legal risks arising from any party denying the signatory, it is advisable to use a qualified e-signature for their evidential value.

Considering that a qualified e-signature is a type of advanced e-signature generated by a qualified e-signature creation device and requires a certificate for e-signatures, it may entail additional expenses such as equipment and service fees when compared to advanced signature services. Organizations using qualified e-signatures bear the annual usage cost based on their operational, technical, and business requirements. Therefore, the provision of qualified e-signature services can lead to significantly higher costs compared to advanced signature services.

Qualified e-signatures may also require the signatory to verify their identity in advance and have the signature key stored inside the qualified e-signature creation device. These devices enable identity verification by means of passwords, allowing certifying authorities to confirm the identity of the signatory.

Given the additional steps for verification, identity confirmation, and authentication required by qualified e-signatures compared to advanced e-signatures, users should conduct a detailed cost-benefit analysis[4] before deciding which type of signature to use. Such an assessment should take into account specific legal regulations, the flexibility of the signatory, security requirements, and the financial situation of the signatory.

For instance, in transactions requiring a high level of security and assurance, such as signing a high-value financial contract, a qualified e-signature may be preferable as it enhances security throughout the process. If; however, the signatory intends to use the documents solely for internal purposes, such as obtaining documents from company employees, then an advanced e-signature may be more suitable.

As explained above, the current E-Signature Law does not differentiate between types of e-signatures and only regulates the type of signature referred to as a qualified e-signature. In other words, within the scope of the E-Signature Law, simple and advanced e-signatures are not considered e-signatures, and therefore, they are not evaluated with the same status as e-signatures in Turkish courts. It should be emphasized here that the use of e-signatures will be considered as evidence as long as the e-signature user meets the criteria set forth in the E-Signature Law.

Usage of E-Signatures in Turkey and Expectations

The utilization of e-signatures in Turkey has been rapidly increasing with each passing day. Currently, e-signatures are widely used in various sectors, and citizens can synchronize their e-signatures with their Turkish identity cards for everyday use. This is made possible through the “Hayat Kimliğinle Kolay” project, which is the second phase of the project launched by the Ministry of Interior’s General Directorate of Population and Citizenship Affairs on 21 September 2020. As of 9 January 2022, population directors in 50 cities across Turkey have started loading e-signatures onto Turkish Identity Cards through “nüfusmatik” devices. Following the initiation of e-signature loading in nüfusmatik devices in 50 cities, e-signature loading services have been made available at Population Directorates, Land Registry Offices, and banks across the country. This application allows citizens to use their new-generation identity cards as driver’s licenses and e-signatures. As a result, e-signatures are now used in various areas, including e-government applications, the National Judiciary Network Project (UYAP), Electronic Public Procurement Platform (EKAP) transactions, e-Attachment Project, Turkish Patent Institute (TPE) processes, Land Registry and Cadastre Information System (TAKBIS), MERNIS processes, submission of bank instructions, and participation in tenders.

From a regulatory perspective; however, it is observed that the E-Signature Law does not fully align with eIDAS. As a result, the legal framework for the implementation of certain e-signature services in Turkey has not yet been clearly defined. This situation presents challenges for Turkish businesses engaged in international commercial activities. For example, e-signatures made through DocuSign do not hold legal validity in Turkish courts because DocuSign[5] signatures do not meet the criteria for a valid e-signature under the E-Signature Law.

Furthermore, even before the era of the “new normal” brought about by the global pandemic, Turkey had shown a strong inclination to increase the use of e-signatures in various sectors, including banking. The 11th Development Plan[6], prepared by the Presidency in July 2019, prioritized the widespread adoption of e-signatures to promote electronic commerce. In line with this goal, it is expected that legal regulations will be amended in the near future to bring them into compliance with eIDAS, aiming to promote paperless trade.

An example of Turkey’s efforts to expand the use of e-signatures is the decision by the Ministry of Commerce to provide tablet computers to customs officials[7]. This initiative aims to enable the signing of legal documents with e-signatures during export procedures, providing both convenience for instant transactions and security, thus marking a significant step toward paperless trade.

Although the Information and ICT seems open to adopting innovations that promote paperless trade, current regulations do not yet contain the necessary provisions for the widespread use of e-signatures. The ICT’s Strategic Plan[8] mentions the goal of reaching an “information society.” In this context, handwritten signatures pose various obstacles for individual financial transactions, leading individuals to prefer conducting their financial transactions through online banking and FinTech products.

According to Article 7 of the Regulation on Consumer Rights in the Electronic Communications Sector issued by the ICT, subscription agreements must be made in writing and signed by the subscriber with a wet signature or a secure electronic signature. By revising the application methods, it is expected that the ICT may amend the current regulation in the near future to change the signature requirement to an “evidenceable declaration of will.”

In conclusion, the current recognition of only qualified e-signatures within the scope of the E-Signature Law and the absence of simple and advanced e-signatures can hinder practicality in processes that could be accomplished with a simpler signature, leading to significant delays. This limited recognition of e-signatures can lead authorized authorities to choose qualified e-signatures despite their higher costs or continue using traditional wet signatures, which are impractical.

If the E-Signature Law is fully or partially amended to align with eIDAS, it will become possible to implement simple and advanced e-signatures. This will enable all relevant organizations and individuals to easily adapt to the European business environment, facilitating a faster integration process.

In such a scenario, the requirement for qualified electronic signatures versus wet signatures can be eliminated, providing a solution for cases where diversity is needed. Recognizing simple and advanced signatures and making them legally valid will reduce operational costs and provide viable solutions for small and medium-sized transactions. Embracing this innovation is the way forward for integration into the “new normal.”

An unexpected development; however, that could challenge these expectations is the Regulation on the Verification Process of the Identity of the Applicant in the Electronic Communications Sector (“Regulation“) issued by the Information and ICT and published in the Official Gazette on 26 June 2021. This regulation introduced changes regarding the use of artificial intelligence in identity verification. For detailed information on the changes introduced by this regulation, you can refer to our Moroğlu Arseven Gazette publication dated 17 August 2021, available via the provided link.

Regarding e-signatures, this regulation explicitly prohibits the use of biometric data, stating that individuals’ biometric data cannot be brought into electronic environments through electronic pens or similar methods. While the ICT enforces a strict ban on biometric signatures, the Personal Data Protection Board emphasized in its decision dated 27 August 2020[9], with reference number 2020/649, that the use of biometric signature data is conditional upon obtaining the explicit consent of the individuals concerned under Article 5 and Article 6 of the Personal Data Protection Law numbered 6698 (“DP Law”) or the fulfillment of the conditions stipulated by the law. Thus, the DP Law left the door open, albeit conditionally, for the use of biometric signatures. It can be argued that the approaches of ICT and DP Law do not align in this regard.

Furthermore, the regulation also determines the burden of proof in administrative and judicial proceedings. According to the regulation, the authorized company providing electronic communication services and/or operating and maintaining the electronic communication network infrastructure is responsible for providing evidence when necessary.

Temporary Article 1 of the regulation states that if three-dimensional signature patterns have already been used in certain documents, they should not be reused, and operator companies and service providers are required to take the necessary measures to comply with the regulation.

In light of all these recent developments and the current approaches of regulatory authorities, it does not appear likely that Turkey will introduce regulations in line with eIDAS in the near future.

References

Anonymous. (2020, February 18). What is an eID (electronic identity)? Signicat. https://www.signicat.com/blog/what-is-an-eid-electronic-identity

Information Technologies and Communication Authority. (2019). 2019-2023 Strategic Plan https://www.btk.gov.tr/uploads/pages/yayinlar-stratejik-planlar/bilgi-teknolojileri-ve-iletisim-kurumu-2019-2023-stratejik-plani-published-revised-at-27-05-19.pdf

DataReportal. (2022). Digital 2022: Global Overview Report. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-global-overview-report

Keser Berber, L. (2019). Biometric Signature and Its Place in Terms of the Written Form Requirement in the Turkish Code of Obligations and the Signature in the Code of Civil Procedure. Istanbul Bilgi University Institute of Informatics and Technology Law https://itlaw.bilgi.edu.tr/media/document/2019/08/biyometrik-imza.pdf

McNeal, D. (2020, Ekim 3). Advanced vs. Qualified eIDAS Electronic Signatures [Guest]. Cryptomathic. https://www.cryptomathic.com/news-events/blog/eidas-electronic-signatures-qualified-vs-advanced-when-to-choose-what-and-why#:~:text=Under%20eIDAS%2C%20an%20Advanced%20Electronic,used%20as%20evidence%20in%20a

Presidency of the Republic of Turkey Strategy and Budget Directorate. (2019). Eleventh Development Plan 2019-2023 www.sbb.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Eleventh_Development_Plan_2019-2023.pdf

Turkish Ministry of Trade, General Directorate of Customs. (2018). Reply to Istanbul Customs Consultants Association Regarding the Topic of ‘Export’. https://cms.gumruktv.com.tr/editor/file/2018/TEMMUZ%202018/27.07.2018/ihracat-islemlerinde-beyannamenin-memur-tarafindan-imzalanmasi-cevabi-yazi.pdf

Personal Data Protection Board. (2020). Decision of the Personal Data Protection Board Regarding the Request for Opinion on the Use of Biometric Signature Data https://www.kvkk.gov.tr/Icerik/6815/2020-649

[1] DataReportal. (2022). Dijital 2022: Global Overview Report. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-global-overview-report

[2] Keser Berber, L. (2019). Biometric Signature and Its Place in Terms of the Written Form Requirement in the Turkish Code of Obligations and the Signature in the Code of Civil Procedure. Istanbul Bilgi University Institute of Informatics and Technology Law https://itlaw.bilgi.edu.tr/media/document/2019/08/biyometrik-imza.pdf

[3] McNeal, D. (2020, Ekim 3). Advanced vs. Qualified eIDAS Electronic Signatures [Misafir]. Cryptomathic. https://www.cryptomathic.com/news-events/blog/eidas-electronic-signatures-qualified-vs-advanced-when-to-choose-what-and-why#:~:text=Under%20eIDAS%2C%20an%20Advanced%20Electronic,used%20as%20evidence%20in%20a

[4] Anonymous. (2020, Şubat 18). What is an eID (electronic identity)? Signicat. https://www.signicat.com/blog/what-is-an-eid-electronic-identity

[5] DocuSign is considered compliant with e-signature standards under eIDAS and is recognized as having evidentiary value.

[6] Presidency of the Republic of Turkey Strategy and Budget Directorate. (2019). Eleventh Development Plan 2019-2023 www.sbb.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Eleventh_Development_Plan_2019-2023.pdf

[7] Turkish Ministry of Trade, General Directorate of Customs. (2018). Reply to Istanbul Customs Consultants Association Regarding the Topic of ‘Export’. https://cms.gumruktv.com.tr/editor/file/2018/TEMMUZ%202018/27.07.2018/ihracat-islemlerinde-beyannamenin-memur-tarafindan-imzalanmasi-cevabi-yazi.pdf

[8] Information Technologies and Communication Authority. (2019). 2019-2023 Strategic Plan https://www.btk.gov.tr/uploads/pages/yayinlar-stratejik-planlar/bilgi-teknolojileri-ve-iletisim-kurumu-2019-2023-stratejik-plani-published-revised-at-27-05-19.pdf

[9] Personal Data Protection Board. (2020). Decision of the Personal Data Protection Board Regarding the Request for Opinion on the Use of Biometric Signature Data https://www.kvkk.gov.tr/Icerik/6815/2020-649